Often the best ideas on community healthcare come from community members themselves—especially when they are engaging in active discussions with healthcare providers and others.

That’s the idea behind community cafes, sponsored by the Alaska State Office of Rural Health (AK-SORH), which are being held in small towns in the state.

“Last spring we told all our Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) that we can come to their communities to facilitate a conversation on whatever topics they want,” said Heidi Hedberg, AK-SORH Director.

“Last spring we told all our Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) that we can come to their communities to facilitate a conversation on whatever topics they want,” said Heidi Hedberg, AK-SORH Director.

The community cafes are set up to last an hour, with the first 25 minutes devoted to a presentation on a chosen topic. Attendees then break into smaller groups for discussion. “We have a facilitator in each small group and a scribe,” Hedberg said. “This is where we are looking for the community to provide feedback on the topic they were just educated on.”

Petersburg Medical Center (PMC) in Petersburg, a small town on an island in southeastern Alaska, was the first to sponsor a community cafe last November at the Petersburg Public Library. Jeannie Monk, Vice President of the Alaska State Hospital and Nursing Home Association, spoke on the changing landscape of healthcare in rural communities and how communities must pivot to accept these changes. Phil Hofstetter, PMC CEO, added his perspective following Monk’s presentation, Hedberg said.

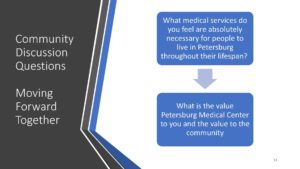

“When we broke into small groups after their presentation, one of the questions we asked was, ‘As a community member, what healthcare services will keep you in your community?’” Hedberg said. “It was fascinating to hear what they want and what they perceive, and their thoughts on healthcare.”

AK-SORH held community cafes twice that day at PMC on the same topic. The morning cafe had 50 to 60 people, and the afternoon cafe had around 30 people participating, Hedberg said. “It’s important that the cafes have a limited number of participants, because in a smaller group, it’s easier to draw out the quiet voices,” she explained. “You could have a town hall meeting, but it would be harder to have one-on-one conversations. In rural communities, the smaller the group, the more information you can draw out of them.”

Hedberg called the first community cafes “a fantastic start,” especially since they included a wide swath of community members. “It enabled us to see where their knowledge base was so that we can target our education and further that conversation,” she said.

PMC, which is Petersburg’s only hospital, is a CAH built in 1917 that was last remodeled 30 years ago, Hedberg said. “One thing we all realized is if Petersburg wants a new hospital it needs to be community-driven,” she said. “And we need to know what services they want so we can build it into that plan.”

The first cafes were such a success that AK-SORH was invited back to PMC in February to do another, this time on the promise of new telehealth offerings. The group experienced a tele-psychiatry visit through a camera, Hedberg said, then broke into smaller groups to answer questions including “what types of services are you looking for?” and “how much would you be willing to pay for these services?” Since then, PMC has launched tele-psychiatry services.

PMC helped advertise the cafes by making posters and putting them in local venues and promoted them on their weekly radio session and their website, which helped lead to their success, Hedberg said.

The idea for AK-SORH’s community cafes sprang from those sponsored by the state’s Office of Substance Misuse and Addiction Prevention (OSMAP), which visited more than 20 Alaskan communities “to educate them on opioids and to hold conversations on how to resolve the issue,” Hedberg said. “From that, a lot of communities formed their own coalitions and OSMAP created a statewide strategy plan drawn out of the responses from those communities.”

“This is not a new idea—it’s just how you organize it,” Hedberg added. “Consensus meetings, listening sessions, community cafes— there’s all different types of them, but for small rural communities, the cafes are a great way to have a structured format to both educate and receive feedback on any topic.” AK-SORH funds its community cafe work through Flex money for travel, and SORH money for staffing time, she said.

Since the cafes that were held in Petersburg, other communities have expressed interest in them, she said.

“It’s exciting when you bring a community together and through that relationship comes feedback, and out of that comes these new service delivery models,” Hedberg concluded. “We’ll continue to do these as long as communities ask us to facilitate these conversations on healthcare topics that are impacting the community—we hope to do these forever!”

————————————————————————————

Does your SORH have a “Promising Practice”? We’re interested in the innovative, effective and valuable work that SORHs are doing. Contact Ashley Muninger to set up a short email or phone interview in which you can tell your story.