By Beth Blevins

Public health students at Oklahoma State University (OSU) are tackling real-life problems at Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) in the state. In collaboration with the Oklahoma Office of Rural Health (OORH), Master of Public Health (MPH) students enrolled in the Designing Public Health Programs course are creating projects that address challenges faced by the hospitals.

“The programs that the students create are in direct response to priorities identified in the hospitals’ Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNAs),” said Lara Brooks, OORH Rural Health Analyst. “The students are divided into groups of two to four during the semester, and they then work on a priority from one of the previous year’s CHNAs.”

The program focuses on CAHs that do CHNAs (particularly nonprofit CAHs, which are required by the IRS to do a CHNA every three years). “Every fall I make a spreadsheet pulling out the priorities identified in the CHNAs and share that with the course instructor, who goes through and weeds it down according to what could be applicable to students in the course,” said Brooks.

This year’s topics addressed sexual health and education for adolescents, smoking cessation, opioid prevention for young adult males, physical activity, healthy lifestyles, and adolescent and parent counseling as prevention for future drug and alcohol abuse. Past programs have included mental health first aid, the creation of a Narcotics Anonymous (NA) group, and a dental hygiene program for nursing home residents.

“The really interesting part is the creativity in the projects,” Brooks said. For example, one group that was assigned “physical activity” as a priority utilized the state parks as an opportunity to get outside. “They went to that community and looked around and saw that the sidewalks aren’t great so they thought outside the box. They visited the nearby state park, got maps, and created a program around being active using the state park.”

Another year, a group from the class created a program on healthy eating that included grocery store tours, working with the local grocery store to host events and to highlight healthy products. “The fresh set of eyes and ideas are what make the collaboration so interesting,” Brooks said.

Brooks visits the students on the first day of class giving them an overview of OORH and its grant programs, describing a CHNA, and talking about common themes and priorities across the state. She then returns on the last day of class when students give their presentations. Brooks also acts as an intermediary between the students and the hospitals since the students do not have time to visit them themselves. She delivers their projects to the hospitals’ CEOs, “making sure they know they can ask follow-up questions,” Brooks said. “At the end, they will have a binder of the program the student group created, along with implementation steps, a budget overview, an evaluation plan, and the students’ own needs assessment.”

The collaboration between OORH and the course creates a three-fold opportunity—for the students, the hospitals, and for OORH. “From the hospital’s perspective, they have the opportunity to have a group of students creating a program just for them,” Brooks explained. “From the student’s perspective, they have the chance to create a real program for a real community to address a real need. And at OORH, we get the opportunity to introduce rural areas of the state to a group of students each spring.”

Stephany Parker, who taught the course this spring, said that the collaboration “brings students and communities closer together in an applied way and opens up communication channels with OORH as an essential resource for public health professionals.” Parker continued, “OORH is our connection to those real-life settings, circumstances and community leaders. The programs and materials students develop are creative, comprehensive, and provide clinic partners with a plan for implementation consideration.”

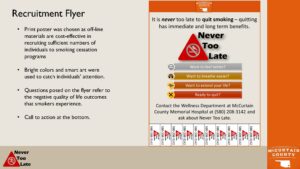

MPH students Andrew O’Neil and Desiree’ Lyon recently created this poster as part of their Designing Public Health Programs at Oklahoma State University.

Andrew O’Neil, a recent student in the course, concurs. “(The course) gave me an understanding of health outcomes, determinants of health, and resources available to implement programming in rural communities, which will be useful as I continue my studies and research addressing rural-urban health disparities,” he said.

So far about 80 students have participated in this coursework/collaboration since its inception in 2016. OORH’s work with this collaboration requires no special funding. “When I deliver the binders to the hospital CEOs, it’s in conjunction with a site visit to the CAH, something that would normally be funded under the Flex program,” Brooks said.

Because OORH is part of the OSU Center for Rural Health, it probably makes a collaboration like this easier, Brooks said. “A program like this is probably easier to replicate with the university-based State Offices of Rural Health since they have that relationship on campus.”

“Nonetheless,” she added, “I know that a lot of folks who work for their state health departments are alumni of public health programs in their states, so if anyone wanted to replicate this it would be fairly simple, just by making a relationship with that program.”